Workout Program For Strength: Unlocking your physical potential requires a strategic approach. This program delves into the science of strength training, exploring the nuances of muscular strength, power, and endurance. We’ll dissect the physiological adaptations triggered by weightlifting, comparing isometric, isotonic, and plyometric techniques. Discover how to craft a personalized 8-week plan, incorporating compound movements and progressive overload for optimal results.

From selecting the right exercises for major muscle groups to understanding the critical role of nutrition and recovery, this guide provides a comprehensive framework for building strength. We’ll address common concerns, such as injury prevention and plateau busting, offering modifications for various fitness levels and age groups. Prepare to transform your physique and unlock unprecedented levels of strength.

Defining “Strength” in Workout Programs

Strength, in the context of workout programs, encompasses more than just the ability to lift heavy weights. It’s a multifaceted physiological capacity reflecting the neuromuscular system’s ability to exert force. Understanding its components is crucial for designing effective and targeted training regimens.

Components of Strength

Strength training programs aim to improve various aspects of strength. These include muscular strength, power, and muscular endurance, each requiring different training methodologies and eliciting unique physiological adaptations. Ignoring these distinctions can lead to suboptimal training outcomes.

Muscular Strength, Power, and Endurance

Muscular strength refers to the maximum force a muscle or muscle group can generate in a single maximal effort. Power, on the other hand, is the rate at which force is produced; it combines strength and speed. Muscular endurance represents the ability of a muscle or muscle group to sustain repeated contractions over time. A weightlifter performing a one-rep max deadlift demonstrates muscular strength, a shot-putter showcases power, and a marathon runner exemplifies muscular endurance.

These three components often interact, but their relative importance varies depending on the sport or activity.

Physiological Adaptations to Strength Training

Strength training induces a cascade of physiological changes that enhance muscle performance. These adaptations are not limited to the muscles themselves; they encompass the nervous system, connective tissues, and even the endocrine system. The body responds to the stress of resistance training by increasing muscle fiber size (hypertrophy), improving the efficiency of neuromuscular activation, and strengthening connective tissues (tendons and ligaments).

Furthermore, hormonal changes, such as increased testosterone and growth hormone levels, contribute to the overall anabolic environment that promotes muscle growth and strength gains. These adaptations are highly specific to the type of training undertaken, emphasizing the importance of selecting appropriate exercises and training parameters.

Types of Strength Training

Several methods exist for improving strength, each targeting specific physiological adaptations. Isometric, isotonic, and plyometric training represent distinct approaches with unique benefits and limitations.

Isometric Training

Isometric training involves generating force against an immovable object, resulting in no change in muscle length. A classic example is holding a plank position. This method primarily improves static strength and can enhance muscular endurance. However, its effects are relatively specific to the joint angle at which the exercise is performed.

Isotonic Training

Isotonic training, also known as dynamic training, involves moving a weight or resistance through a range of motion. This is the most common type of strength training, encompassing exercises like bicep curls or squats. Isotonic training improves both strength and endurance, offering a more versatile approach compared to isometric training. Variations in speed and resistance can further tailor the training stimulus.

Plyometric Training

Plyometric training focuses on explosive movements that utilize the stretch-shortening cycle. Examples include box jumps and medicine ball throws. This method enhances power production by leveraging elastic energy stored in the muscles and tendons during the eccentric phase of movement. Plyometric training is particularly beneficial for athletes requiring rapid bursts of power. However, it carries a higher risk of injury and requires proper technique and conditioning.

Designing a Strength Training Program: Workout Program For Strength

Effective strength training programs are built on a foundation of progressive overload, proper exercise selection, and consistent execution. A well-structured program considers the individual’s experience level, goals, and available resources, ensuring both safety and efficacy. Ignoring any of these crucial elements can lead to plateaus, injuries, or a complete lack of progress.

An 8-Week Beginner Strength Training Program

This program focuses on building a foundational level of strength and familiarity with key exercises. It emphasizes proper form over heavy weight. Remember to consult a healthcare professional before starting any new exercise regimen.

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Rest (seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Squats | 3 | 8-12 | 60-90 |

| Push-ups (on knees if needed) | 3 | As many as possible (AMRAP) | 60 |

| Rows (dumbbell or barbell) | 3 | 8-12 | 60-90 |

| Overhead Press (dumbbell or barbell) | 3 | 8-12 | 60-90 |

| Plank | 3 | 30-60 seconds | 60 |

This program should be performed twice per week, with at least one day of rest between sessions. Focus on maintaining proper form throughout each exercise. As strength increases, consider gradually increasing the weight, reps, or sets.

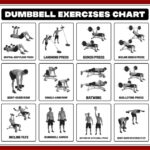

Strength Training Program Focusing on Compound Movements, Workout Program For Strength

Compound exercises, which engage multiple muscle groups simultaneously, are crucial for building overall strength and maximizing calorie expenditure. This program prioritizes these movements for efficient and effective gains.

Squats: Target the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes. Proper form involves keeping the back straight, chest up, and squatting until the thighs are parallel to the ground. Variations include barbell back squats, front squats, and goblet squats.

Deadlifts: A full-body exercise working the back, hamstrings, glutes, and forearms. Maintaining a neutral spine and engaging the core are essential for preventing injury. Variations include conventional deadlifts, sumo deadlifts, and Romanian deadlifts.

Bench Press: Primarily targets the chest, shoulders, and triceps. Lie flat on a bench, keeping feet flat on the floor and maintaining a stable core. Variations include incline bench press and decline bench press.

Overhead Press: Works the shoulders, triceps, and upper back. Maintain a stable base and avoid arching the back. Variations include dumbbell overhead press and barbell overhead press.

Bent-Over Rows: Targets the back muscles, particularly the lats and rhomboids. Maintain a straight back and avoid rounding the shoulders. Variations include barbell rows and dumbbell rows.

Incorporating Progressive Overload Principles in Strength Training

Progressive overload is the cornerstone of long-term strength gains. It involves consistently increasing the demands placed on the muscles over time. This can be achieved by manipulating several variables:

Increasing Weight: Gradually adding weight to the bar or dumbbells as you become stronger. A common approach is to increase the weight by 2.5-5 pounds (1-2.5 kg) when you can comfortably complete all sets and reps with good form.

Increasing Reps: If you can easily complete all sets and reps with the current weight, increase the number of repetitions per set. For example, if you’re doing 8 reps, try increasing to 10-12.

Increasing Sets: Adding an extra set to your workout once you’ve mastered the current weight and rep scheme. If you’re doing 3 sets, try increasing to 4 or 5.

Decreasing Rest Time: Reducing the rest period between sets can increase the intensity of your workout and stimulate further muscle growth. However, ensure sufficient rest to maintain proper form.

Introducing Advanced Techniques: Incorporating techniques such as drop sets, supersets, or rest-pause sets can further challenge the muscles and promote growth. These techniques should only be used once a solid foundation has been established.

“Progressive overload is not about lifting heavier weights every single workout; it’s about consistently challenging your muscles over time to stimulate growth.”

Program Variations and Individual Needs

Adapting a strength training program to suit individual needs is crucial for maximizing results and minimizing injury risk. Factors such as age, fitness level, pre-existing conditions, and personal goals significantly influence program design. A one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective; instead, a personalized plan ensures safety and efficacy.Program modifications should consider progressive overload, a fundamental principle of strength training. This involves gradually increasing the weight, repetitions, or sets over time to continuously challenge the muscles.

However, the rate of progression should be tailored to the individual’s capabilities and recovery capacity.

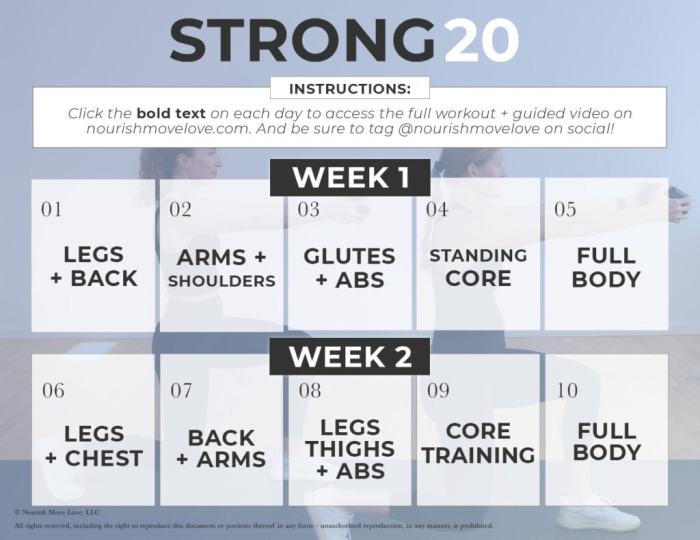

Modifying Programs for Different Fitness Levels

Individuals new to strength training should start with lighter weights and fewer repetitions, focusing on proper form. A beginner’s program might involve one set of 8-12 repetitions for each exercise, performed twice a week. As strength increases, the weight, sets, or repetitions can be gradually increased. Conversely, experienced lifters can incorporate advanced techniques like drop sets, supersets, or plyometrics to further challenge their muscles.

For example, a seasoned lifter might perform three sets of 6-8 repetitions with heavier weights, using advanced techniques to push their limits. Regular assessment of progress and adjustments to the program are essential for continued improvement.

Strength Training for Older Adults

Strength training is particularly beneficial for older adults, helping to maintain muscle mass, bone density, and balance, thus reducing the risk of falls and fractures. However, age-related changes such as decreased muscle mass and joint mobility require program modifications. A program for older adults should prioritize proper form and focus on functional exercises that mimic everyday movements. Lighter weights and higher repetitions (10-15) are often recommended, with a focus on controlled movements and adequate rest periods.

Incorporating balance exercises and flexibility training is also crucial. For instance, a program could include chair squats, wall push-ups, and light dumbbell rows, alongside exercises focused on improving balance, such as standing on one leg or tai chi movements. A qualified fitness professional can assess an individual’s capabilities and create a safe and effective program.

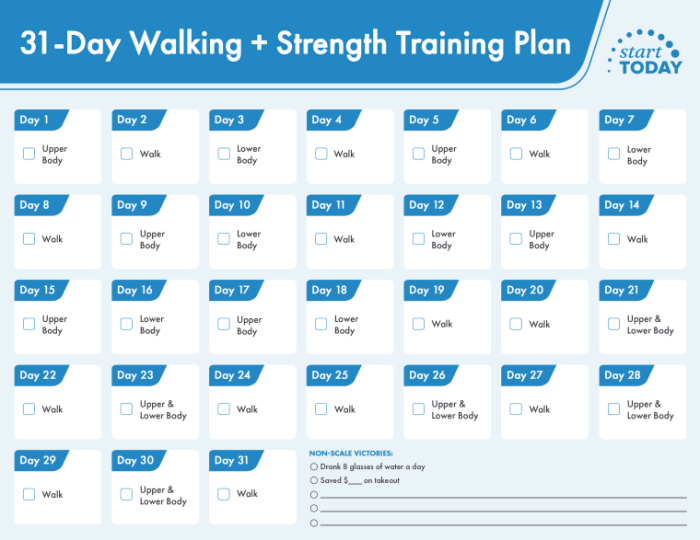

Integrating Strength Training and Cardiovascular Exercise

Combining strength training with cardiovascular exercise provides holistic fitness benefits. A balanced program can involve alternating strength training days with cardio days, or incorporating short bursts of cardio between strength training sets (circuit training). The specific type and intensity of cardio should be chosen based on individual fitness levels and preferences. For example, a program might involve strength training three days a week and moderate-intensity cardio (brisk walking, cycling) on the other days.

Circuit training could involve performing a strength exercise, followed by a short period of cardio, such as jumping jacks or burpees, before moving on to the next strength exercise. This approach improves both strength and cardiovascular fitness efficiently.

Tracking Progress and Making Adjustments

Consistent monitoring of progress is crucial for optimizing strength training results. Without tracking, identifying areas for improvement or recognizing plateaus becomes significantly more challenging. Effective tracking facilitates informed adjustments, ensuring continued progress and minimizing the risk of injury.Effective tracking methods provide quantifiable data that reflects the efficacy of the program. This data allows for objective analysis and informed decisions regarding program adjustments, ensuring the program remains challenging yet sustainable.

Ignoring progress tracking can lead to stagnation or even regression.

Methods for Tracking Strength Training Progress

Several methods can effectively track progress in a strength training program. A combination of approaches often provides the most comprehensive overview. Choosing the right methods depends on individual preferences and the specific goals of the training program.

- Weight Lifted: Recording the amount of weight lifted for each exercise is a fundamental method. This directly measures strength gains. For instance, consistently increasing the weight used in a squat indicates improved strength.

- Repetitions Completed: Tracking the number of repetitions (reps) performed at a given weight is another key indicator. Increasing reps at a consistent weight shows improved muscular endurance and strength. For example, moving from 8 reps to 12 reps on bench press at the same weight signifies progress.

- Sets Completed: Monitoring the number of sets performed provides additional context. Increasing sets at a given weight and rep range demonstrates enhanced work capacity.

- One-Rep Maximum (1RM): Periodically testing the 1RM—the maximum weight that can be lifted for one repetition—provides a benchmark of overall strength. Increases in 1RM clearly indicate significant strength gains.

- Body Measurements: While not a direct measure of strength, tracking body measurements such as circumference of major muscle groups can provide supplementary evidence of progress. Increased muscle size often correlates with increased strength, although not always directly proportional.

- Training Logs/Journals: Maintaining a detailed training log is essential. This log should include the date, exercises performed, weight used, reps completed, sets completed, and any subjective notes regarding fatigue, soreness, or other relevant observations. This detailed record enables consistent monitoring and the identification of trends.

Identifying and Addressing Plateaus

Plateaus are inevitable in strength training. They represent periods where progress stalls despite consistent effort. Recognizing and addressing plateaus requires a systematic approach, focusing on program modifications rather than simply increasing training volume.Identifying a plateau typically involves observing a lack of progress in key metrics over several weeks. For instance, if the weight lifted or reps completed remain unchanged despite consistent effort, a plateau may be occurring.

This necessitates strategic program adjustments.

Program Adjustments Based on Individual Needs and Recovery

Listening to the body is paramount in strength training. Ignoring signs of fatigue or pain can lead to injury and hinder progress. Adjustments should always consider individual needs and recovery capabilities.

- Rest and Recovery: Adequate rest and recovery are crucial for muscle growth and repair. Insufficient rest can lead to overtraining, hindering progress and increasing injury risk. Signs of overtraining include persistent fatigue, decreased performance, and increased susceptibility to illness.

- Progressive Overload: Gradually increasing the demands placed on the body is essential for continued strength gains. This can involve increasing weight, reps, sets, or frequency. However, this should be done gradually to avoid injury and ensure proper recovery.

- Exercise Variation: Introducing variations in exercises can stimulate muscle growth and prevent plateaus. This can involve using different exercise variations or changing the order of exercises within a workout.

- Nutrition and Hydration: Proper nutrition and hydration are vital for muscle recovery and growth. A balanced diet with adequate protein intake is essential for muscle repair and growth. Staying properly hydrated also supports optimal muscle function.

Building strength is a journey, not a sprint. This program equips you with the knowledge and tools to design a personalized plan that aligns with your goals and fitness level. By understanding the principles of progressive overload, proper form, and the importance of recovery, you can safely and effectively build muscle, increase power, and enhance overall fitness. Remember to listen to your body, track your progress, and adapt your program as needed.

The path to strength is paved with consistency, dedication, and a smart training approach.