Good Strength Training Workouts are more than just lifting weights; they’re a pathway to improved physical and mental well-being. This guide delves into the science and art of crafting effective strength training programs, tailored to individual needs and goals. We’ll explore various training philosophies, essential exercises, and programming principles to help you build strength, increase muscle mass, and enhance overall fitness.

Understanding the nuances of progressive overload, periodization, and proper form is crucial for maximizing results and minimizing injury risk. We’ll also address nutrition and recovery strategies vital for optimal performance.

From beginner-friendly routines to advanced techniques like drop sets and supersets, we’ll equip you with the knowledge and tools to design a strength training program that aligns with your aspirations. This comprehensive guide aims to empower you to take control of your fitness journey, achieve your goals, and enjoy the transformative power of consistent, well-structured strength training.

Programming Principles for Effective Workouts

Effective strength training programs rely on several key principles to maximize results and minimize the risk of injury. Understanding and implementing these principles is crucial for achieving consistent progress and reaching individual fitness goals. This section will detail the importance of progressive overload, periodization, and the selection of appropriate training splits.

Progressive Overload

Progressive overload is the cornerstone of any successful strength training program. It simply refers to the gradual increase in training demands over time to continuously challenge the muscles and stimulate further growth and strength adaptations. This can be achieved by increasing the weight lifted, the number of repetitions performed, the number of sets, or decreasing rest periods between sets.

For example, a beginner might start with bench pressing 10 repetitions of 100 pounds for three sets. Over several weeks, they could progressively increase this to 12 repetitions of 100 pounds, then 10 repetitions of 110 pounds, and so on. Another method is to introduce more challenging exercises. If a lifter has mastered squats with a barbell, they might progress to front squats or Bulgarian split squats to further stimulate muscle growth.

Failure to progressively overload will eventually lead to a plateau in strength gains.

Periodization

Periodization is a systematic approach to training that involves cycling the intensity and volume of training over time. This cyclical approach allows for periods of high-intensity training focused on strength development, interspersed with periods of lower intensity training for active recovery and injury prevention. A common periodization model is the linear periodization model, where intensity gradually increases over several weeks or months, culminating in a peak performance period.

Conversely, undulating periodization involves varying the intensity and volume within a week or even within a single training session. For instance, a periodized program might incorporate a hypertrophy phase (high volume, moderate intensity) followed by a strength phase (low volume, high intensity), and finally a peaking phase (very low volume, very high intensity) before a competition or important event.

This planned variation prevents overtraining and optimizes strength gains over the long term. Consider a marathon runner: they wouldn’t run at their maximum speed every day; instead, they incorporate easy runs, tempo runs, and interval training throughout their training plan.

Training Splits, Good Strength Training Workouts

Different training splits offer varying advantages depending on individual goals, training experience, and recovery capacity. Upper/lower splits, for instance, divide training into upper body and lower body workouts on alternating days. This allows for adequate rest for each muscle group. Push/pull/legs splits categorize exercises based on the movement pattern (pushing, pulling, or leg exercises) and allows for greater specialization and focus on individual muscle groups.

Full-body workouts, on the other hand, train all major muscle groups in each session. This is ideal for beginners or individuals with limited time. The choice of split depends on individual needs and preferences. A highly trained athlete might benefit from a more specialized split like push/pull/legs, while a beginner might find a full-body routine more effective and less demanding.

An experienced lifter may choose a split that allows for higher training frequency for certain muscle groups, while a novice lifter may benefit from a less frequent approach to allow for greater recovery.

Nutrition and Recovery for Optimal Results

Maximizing the benefits of a strength training program requires a holistic approach that extends beyond the gym. Nutritional strategies and recovery methods play a crucial role in optimizing muscle growth, reducing the risk of injury, and ensuring sustainable progress. Ignoring these aspects can significantly hinder results, leading to plateaus or even setbacks.Dietary Requirements for Muscle Growth and RecoveryAdequate nutrition fuels muscle protein synthesis, the process by which your body repairs and builds muscle tissue after workouts.

This requires a balanced intake of macronutrients—protein, carbohydrates, and fats—along with essential micronutrients. Insufficient intake of any of these can limit gains and increase recovery time.

Macronutrient Intake for Strength Training

The optimal macronutrient ratio varies depending on individual factors such as training intensity, body composition goals, and metabolic rate. However, a general guideline for strength training individuals involves prioritizing protein intake. Protein provides the building blocks for muscle repair and growth. Carbohydrates provide the energy needed for intense workouts and replenish glycogen stores. Healthy fats support hormone production and overall health.

- Protein: Aim for 1.6-2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily. This can be achieved through lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, and plant-based protein sources like tofu and tempeh. Prioritize consuming protein within 30-60 minutes post-workout to maximize muscle protein synthesis.

- Carbohydrates: Consume carbohydrates to fuel workouts and replenish glycogen stores. Choose complex carbohydrates such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables over refined carbohydrates like white bread and sugary drinks. The amount of carbohydrates needed will vary depending on training volume and intensity.

- Healthy Fats: Include sources of healthy fats like avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil in your diet. These fats are essential for hormone production and overall health.

Sample Meal Plan

This sample meal plan provides a general guideline and should be adjusted based on individual needs and preferences. Calorie and macronutrient targets should be determined through consultation with a registered dietitian or certified nutritionist.

- Breakfast: Oatmeal with berries and nuts, and a side of eggs.

- Lunch: Grilled chicken salad with mixed greens, quinoa, and a light vinaigrette.

- Dinner: Baked salmon with roasted vegetables and brown rice.

- Snacks: Greek yogurt with fruit, protein shake, trail mix.

Importance of Sleep, Stress Management, and Hydration

Beyond nutrition, recovery encompasses sleep, stress management, and hydration. These factors significantly influence muscle recovery and overall well-being.Sleep deprivation hinders muscle protein synthesis and impairs the body’s ability to recover from intense workouts. Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which can catabolize muscle tissue. Adequate hydration is crucial for nutrient transport, temperature regulation, and overall bodily function.

Sufficient sleep (7-9 hours per night), effective stress management techniques (e.g., meditation, yoga), and consistent hydration are as important as training and nutrition for optimal results.

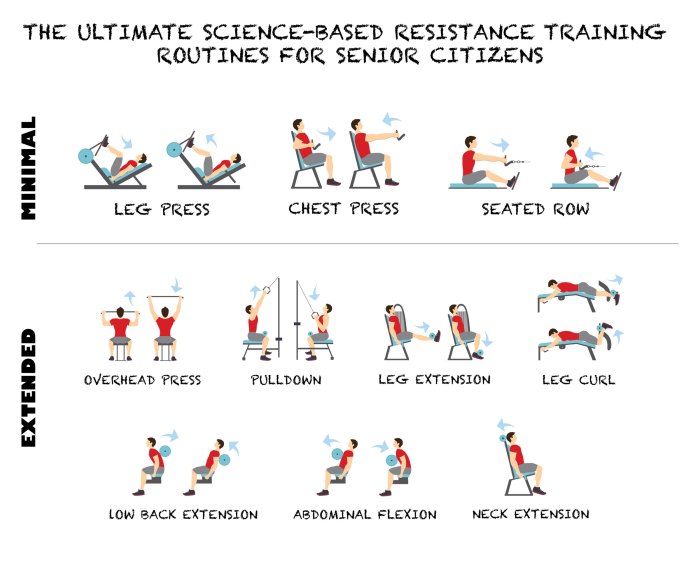

Visual Representation of Exercises: Good Strength Training Workouts

Effective strength training requires a thorough understanding of proper exercise form. Visualizing the movement, muscle activation, and joint mechanics is crucial for maximizing results and minimizing injury risk. This section provides detailed descriptions of key compound exercises, focusing on the biomechanics involved.

Squat

The squat is a fundamental compound movement targeting primarily the quadriceps, glutes, and hamstrings. The barbell back squat, for instance, begins with the barbell resting across the upper trapezius muscles. The feet should be shoulder-width apart, with toes slightly pointed outward. As the lifter descends, the hips and knees flex simultaneously, maintaining a neutral spine. The depth of the squat should ideally allow the thighs to become parallel or slightly below parallel to the ground.

During the concentric phase (the upward movement), the lifter extends the hips and knees, returning to the starting position. Throughout the movement, core engagement is vital to maintain spinal stability. Muscle activation progresses from the lower back and core stabilizing the spine initially, followed by the quadriceps and glutes extending the knee and hip joints to drive the lifter upwards.

Bench Press

The bench press primarily targets the pectoralis major, anterior deltoids, and triceps brachii. The lifter lies supine on a bench, grasping the barbell with an overhand grip, slightly wider than shoulder-width apart. The lifter lowers the barbell to the chest, maintaining a controlled descent, touching the chest lightly. During the concentric phase, the lifter extends the elbows, pushing the barbell back to the starting position.

Throughout the movement, scapular retraction (pulling the shoulder blades together) is important to maintain shoulder stability. The triceps brachii are responsible for the elbow extension, while the pectoralis major and anterior deltoids work synergistically to adduct and horizontally flex the shoulder joint.

Deadlift

The deadlift is a powerful compound exercise engaging numerous muscle groups, including the erector spinae, gluteus maximus, quadriceps, and hamstrings. The lifter stands with feet hip-width apart, positioned directly over the barbell. The lifter initiates the lift by extending the hips and knees simultaneously, keeping the back straight and core engaged. The barbell remains close to the body throughout the lift.

The lifter continues extending the hips and knees until the barbell is fully extended. During the concentric phase, the lifter drives upwards through the legs and hips, returning the barbell to the ground under control. The entire posterior chain is activated, from the lower back and glutes extending the hips to the hamstrings and calves assisting in the knee extension.

Barbell Squat vs. Goblet Squat

The key differences between a barbell back squat and a goblet squat lie in the center of gravity, muscle activation patterns, and overall difficulty.

The barbell squat, due to the weight being positioned on the upper back, places more stress on the lower back and requires significant core stability. The goblet squat, with the weight held close to the body, reduces stress on the lower back and allows for a more upright torso, making it generally more accessible to beginners. While both exercises primarily target the quadriceps, glutes, and hamstrings, the goblet squat may emphasize the quadriceps more due to the altered center of gravity.

The barbell squat often necessitates greater overall strength and stability.

Building a successful strength training program requires a holistic approach encompassing proper exercise selection, progressive overload, strategic periodization, and mindful attention to nutrition and recovery. By understanding the principles Artikeld in this guide, and adapting them to your individual needs and goals, you can unlock your full strength potential. Remember, consistency and patience are key. Embrace the journey, celebrate your progress, and enjoy the rewarding experience of building a stronger, healthier you.